News

News

~1 137 words | 6 934 characters | Reading time: ~ 3 minutes

Will social cohesion solve the problem of radical extremism?

Social cohesion is assumed to be the cure for radical extremism. This assumption is made by the originators of projects to increase its level and the governments paying for these projects. But is this the case? The question is answered by Micaela Varela, Dominika Bulska, Rezarta Bilali and Rouxi Xu in the article “Does Social Cohesion Predict Justification of Extremist Violence? Evidence From the Sahel Region in Burkina Faso,” published in the European Journal of Social Psychology. The authors point out that there is a link between cohesion and acceptance of radical extremism.

INTRODUCTION | Burkina Faso lies at that point on the map of Africa where the yellow color of the Sahara turns into the ever-green color of the savannah. Geographers call it the Sahel and it extends to many countries – Niger, Mali, Sudan and also Burkina, where the Sahel is one of the northern administrative regions. Burkina is a diverse country both climatically and socially. It is inhabited by at least ten ethnic groups with names that say nothing – such as Mossi, Fulani, Gurunsi. Linguistic differences are superimposed on cultural ones, and religious ones on top of them. While almost every Fulani professes Islam, one in three Mossi may profess Christianity or one of the traditional animist religions. It seems that all the people of Burkina Faso, who refer to themselves as “Burkinabé”, are united only by the dry ground on which they daily walk.

Yet, they share something more in common. The Burkinabés are struggling with economic problems, disease and poverty, but not only that. While Mossi or Fulani may not tell us anything, ISIS, jihadists or Boko Haram already do. Terrorist organizations are active all over the Sahel, so the daily bread of a Burkina Faso resident is radical extremism, well, unlike that of wheat. The global terrorism index is 8.571 (for comparison: for Afghanistan, it’s 7.83), so the Polish Foreign Ministry politely “advises against all travel” to the Sahel region in particular.

Yet, they share something more in common. The Burkinabés are struggling with economic problems, disease and poverty, but not only that. While Mossi or Fulani may not tell us anything, ISIS, jihadists or Boko Haram already do. Terrorist organizations are active all over the Sahel, so the daily bread of a Burkina Faso resident is radical extremism, well, unlike that of wheat. The global terrorism index is 8.571 (for comparison: for Afghanistan, it’s 7.83), so the Polish Foreign Ministry politely “advises against all travel” to the Sahel region in particular.

No one would be happy to see their country hold the top spot on this list, so efforts are being directed toward raising social cohesion. Is this a good strategy?

“Many governments have invested in interventions that foster social cohesion to promote peace and prevent the rise of violent extremism” – Varela, Bulska, Bilali oraz Xu write – “Yet, we know little about the relationship between social cohesion and support for violent extremism.”

Social cohesion functions like gravity – you can’t seem to see it, but it holds us together. It makes us not break up into thousands of one-person planets called “I”, but merge into small galaxies. “I am a resident of this city,” ”I am an employee of this workplace.” Galaxies can overlap “I am a resident of this city and I am a parent.” The more galaxies the “I” belongs to, the greater the social cohesion. And cohesion has a huge impact on the life of both the individual and the entire community.

“Social cohesion is seen as a key to the functioning of societies.” – Varela, Bulska, Bilali i Xu (2025).

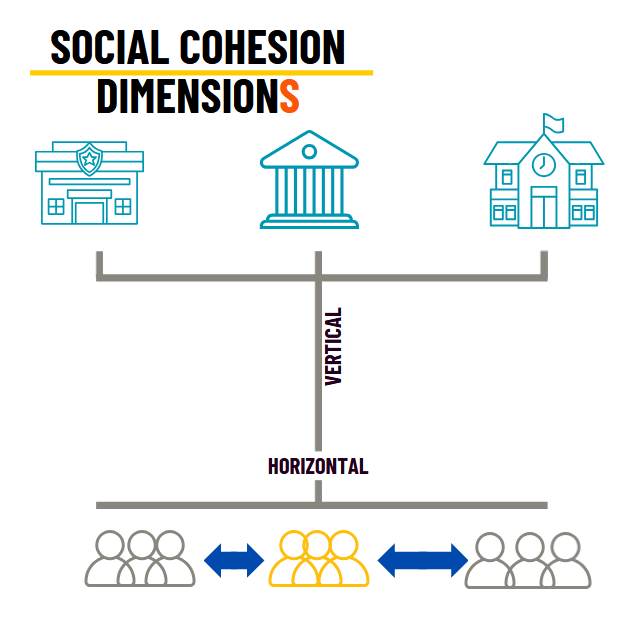

Psychology says that the components of social cohesion are “trust, a sense of belonging and a willingness to participate in community activities,” and distinguishes two types of it. While a neighborhood community or ethnic group is the so-called horizontal (so-called horizontal) type of social cohesion, vertical (so-called vertical) cohesion is expressed through trust in the actions of state institutions. If citizens trust that their taxes are well managed (e.g., funding road maintenance or paying for a public school) and engage in public life (e.g., by going to the polls), then the rate of vertical cohesion is high.

Psychology says that the components of social cohesion are “trust, a sense of belonging and a willingness to participate in community activities,” and distinguishes two types of it. While a neighborhood community or ethnic group is the so-called horizontal (so-called horizontal) type of social cohesion, vertical (so-called vertical) cohesion is expressed through trust in the actions of state institutions. If citizens trust that their taxes are well managed (e.g., funding road maintenance or paying for a public school) and engage in public life (e.g., by going to the polls), then the rate of vertical cohesion is high.

The thought of a country with high cohesion evokes a postcard image from Scandinavia, where a house can be left unlocked, where a child gets a kindergarten slot regardless of skin color, where a civic budget is discussed, and where going out to buy rolls doesn’t turn into a quest for the golden fleece. In low-index countries, the opposite is true. In a country with low cohesion, even collecting data is an act of courage.

A study by Varela, Bulska, Bilali and Xu (2025)

So how to test the link between social cohesion and radical extremism? It would be easy to hand out questionnaires to first-year students, but in psychology we do not complain about the scarcity of such studies. Much rarer are field studies. And so Varela, Bulska, Bilali and Xu found themselves in Burkina Faso 🇧🇫.

PREDICTIONS | The researchers predicted that:

PREDICTIONS | The researchers predicted that:

- Vertical social cohesion and intergroup social cohesion should be associated with lower justification of violence.

- Sense of community should be associated with lower justification of violence.

MEASUREMENT | Acceptance of violence was measured by asking respondents about their agreement with the statements: “The use of violence can never be justified” or ”Violence is not an effective means of solving problems.” Cohesion is a key concept in this study, measured on several levels – trust, sense of community, and community involvement. Different aspects of cohesion were examined by asking about the frequency of attendance at meetings, the degree of trust in different groups, or compliance with statements such as “I feel a member of this community.” With this approach, it was possible to check the level of horizontal cohesion, both internal and external, as well as vertical.

RESULTS | The survey data tell us that almost all aspects of social cohesion included in the study are associated with lower acceptance of radical extremism. The devil is in the details, because “almost” makes a difference.

Contrary to predictions, one aspect of cohesion – community engagement – was associated with higher justification of extremist violence, both at the individual and village levels, and both cross-sectionally and longitudinally. What does this mean? If someone is actively involved in the community, he or she is more accepting of violence as a way of solving problems than someone who just takes care of his or her own homestead – and it didn’t matter what village the respondent was in.

“This is not the first empirical study that links higher community participation to more support for extremist violence” – researchers notice.

After all, what does the word “community” mean? After all, parents of kindergarteners, residents of a housing estate, members of a housewives’ circle – and gang members – will tell you about belonging to a group. Perhaps what reverses the expected correlation is the nature of the community.

Another interesting phenomenon observed in the survey is the disappearance of dependency, which, while it was present when individuals were surveyed, disappeared when entire villages were analyzed. For those surveyed, trust in state institutions, that vertical dimesion of a social cohesion, was associated with lower acceptance of violence. Meanwhile, at the village level – this correlation was no longer. How to explain this fact? The researchers speculate that institutional trust may not be something that justifies radical extremism.

🏁 TAKE HOME MESSAGE…. | The difference between assumptions and reality can sometimes be large and painful, including financially. This time, the results of the study may reassure the originators of increasing the degree of cohesion. “Building intergroup trust and a sense of community reduces the desire to resort to violence as a means of solving problems,” – says Dominika Bulska, author of the study and a member of the PSPS society.

Also used:

- Institute for Economics & Peace (2024). Global Terrorism Index Briefing. https://www.visionofhumanity.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/GTI-2024-Briefing-web.pdf [GTI of Burkina Faso and Afganistan]

- Africa’s map was created with mapchart.net

- Picture on a main page: Lili/Canva

DOMINIKA BULSKA

PhD in Psychology, member of the SWPS Center for the Study of Social Relationships. In her research work, she asks the question of factors affecting intergroup relations.

Views: 6